We are a group of creative people who help organizations make their ideas beautiful.

Tyson Foersterling

When Tyson Foersterling was a young boy growing up in Branson, Missouri, he would sit outside on the back porch and wait for his dad to get home from his job as a park ranger.

In early summer in that part of the Ozarks the evenings seem to fall like fog from the hilltops. And with the cooler air and the falling darkness come the sounds of frogs and crickets and nightjars, maybe the low hoot of a barred owl from over by the lake.

Tyson would sit beneath this canopy of dusk and noise, waiting patiently for another sound: the sharp gargle of Glasspack mufflers on his dad’s GMC truck. “I’d hear that noise from a long way off,” he remembers. “From all the way at the bottom of the hill. Our hunting beagles would start barking like crazy, and that was the sign that it was time to go fishing.”

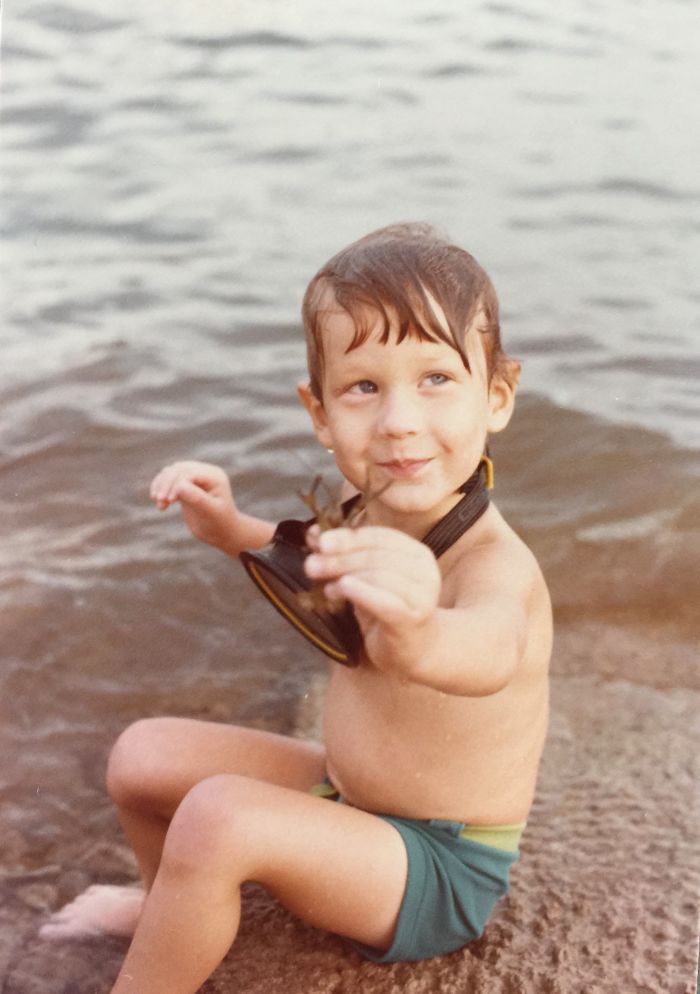

Catching crawdads at Table Rock Lake. "I might have decided to put that crawdad in my mask and dive for more."

The Foersterling family--Ken, Carolyn, Tyson and his older brother Brett--lived about five minutes away from both Table Rock Lake and Lake Taneycomo, so fishing was integral to their lives. “We’d load up the boat and go to Taneycomo to drift-fish for trout. Or we’d put in at Table Rock and go bass fishing.”

During the summer, Tyson would stay with his grandpa in Warsaw, MO., and hunt squirrels. When it got cold, they’d hunt rabbits. He cleaned his own guns and loaded his own shells. In junior high, he was finally allowed to join the men in the deer hunt. “That’s one of my most memorable moments, being 13 and getting up before the sun, freezing in the deer stand. I wouldn’t take any of that away.”

Decades later, hunting is no longer part of his life. But his father’s love of the outdoors definitely took root, along with other personality traits Tyson himself seems almost not to notice, but which are plain to anyone who knows him. Foremost among these are commitment and loyalty.

Decades later, hunting is no longer part of his life. But his father’s love of the outdoors definitely took root, along with other personality traits Tyson himself seems almost not to notice, but which are plain to anyone who knows him. Foremost among these are commitment and loyalty.

Ken spent his entire career with the Corp of Engineers, rising from Park Ranger to Operations Manager for the Table Rock Project, overseeing the entire lake. “One of his duties was dealing with politicians, developers and residents that wanted to build on or near the lake,” Tyson says. “And he felt a responsibility to protect it from over-development and keep it as beautiful as possible. He just loved taking care of it, and taking care of the people who used it.”

Occasionally, the job had more somber demands. “When bad things happened, like If there was a boating accident on the lake, or a drowning, my dad was often one of the first people they called,” Tyson says. “I remember driving out at night with him to search for the scene of an accident.”

But it was the only job his dad ever had, and by all accounts, he never really considered doing anything else.

Tyson and his wife, Andrea, now live in Portland, Oregon, with their two daughters: Riley (12) and Sadie (10). However, the day we did our phone interview, Tyson revealed that he was actually back in Branson for a family visit, and was talking to me from the same back porch of the same house where he used to sit and wait for his dad, all those years ago. It’s the only house his parents have ever lived in, at least in Tyson’s lifetime. It’s clear he and his brother grew up in a home filled with stability, tradition and a firm sense of place.

This may help to explain why Tyson, unlike most advertising creatives, has spent almost his entire career with one agency.

“When I started at Paradowski, I think I was maybe the 17th person in the agency,” he remembers. This was back in 2001, not long after the agency celebrated its 20th anniversary. It was still owned and operated by the founder, Alex Paradowski, and his wife, Nila.

“I had a friend from college who worked there, and he said I should come in for an interview but that I should know it’s a shirt-and-tie kind of place. All the designers wore ties. It was very different. Very quiet, very formal. So I called Alex Paradowski and asked him if he’d look at my portfolio and he said, ‘Sure, come on in.’ Then I asked him if he was hiring and he said, ‘No.’ And that was him, in a nutshell.”

But the interview went well and, after a harrowing, all-agency follow-up interview (“I walked in and there were 16 people sitting around the table, waiting to grill me.”), he was hired as a graphic designer. Seventeen years later, he’s the agency’s longest-tenured Creative Director, overseeing his own creative team and managing our largest client.

During his years at Paradowski, it has morphed from a 17-person design studio into an 80-person creative services agency. The ownership has changed. The office has moved. Twice. I asked Tyson a very blunt question: Why did you stay?

He pauses for a second and then sighs. Tyson is unfailingly polite, but it’s clear my question annoys him slightly.

“Well, Brad, I like to think that I helped build this place. I didn’t want to just walk away. Sure, those thoughts go through your head when times are tough. But I had a lot of pride in the fact that there were still people here that I trusted and liked, and there was still a lot worth saving.”

As soon as Tyson says this, I have an embarrassing epiphany. I realize that I was asking the question as though all these changes were something that happened to Tyson, and not an evolution that he helped to bring about. Tyson is not someone who feels the need to constantly remind you of his importance, or his tenure. His humility and kindness can sometimes mask the fact that he has, in fact, been one of the main architects of Paradowski culture and growth.

Almost every designer in the agency has benefitted from Tyson’s mentorship and critique. It’s a hard line to walk, managing creative talent. You have to allow for autonomy and self-expression (you’re paying them to think and create, after all), but you also have to make dozens of hard choices every day, often under a lot of pressure. Some ideas are simply not going to work, and you have to be willing to say so.

“Before I give feedback, I always ask myself: ‘Is this something I would appreciate hearing?’ That doesn’t mean I’m not going to give someone negative feedback. I just means, am I structuring it in a way that’s going to be helpful.”

“I think I’m pretty good at reading people,” he says. “I’m not always the best at talking or presenting, perhaps. I get nervous. But I do think I’m a good listener. I’m looking for a connection with each member of my team. What kind of feedback is most useful for them? Do they need to be challenged directly, or do they need more confidence? Most of the time, I find, they just need a chance to talk through it with me, and they eventually find the right solution themselves. They just need someone to listen.”

According to Tyson, recognizing a good idea is really a matter of feel. You have to do your research, you have to understand the strategy. But after that, it’s best to open yourself up to the possibility of excitement.

“A good idea just causes something to click in your brain. When someone presents a truly great and original idea to me, there’s just a turn that happens where I say: I wouldn’t have thought about it that way. I can literally feel a change in myself. I can’t tell you exactly what it is, but a few minutes ago it didn’t exist, and now it does.”

Tyson and Andrea both had parents who taught them the value of balance. Tyson’s dad instilled an ethic that can best be described as: Work hard and play hard. The work comes first, but that doesn’t mean it’s more important. You work so you can play. When it’s time to play, don’t waste it.

This is part of the reason they decided to move to the Pacific Northwest to raise their girls. They been there for seven years now, and all of their free time is spent outdoors biking, hiking, fishing and enjoying what nature provides.

Portland isn’t Branson; the politics are different and the coffee is better. But just like his father, Tyson is enjoying the satisfaction that comes from commitment to a place, and loyalty to a workplace that represents more than just a job.

And every night, as the birds start their chatter in the late and failing light of another Portland sunset, Riley and Sadie listen for the click of a laptop closing. They listen for the soft thudding of feet on the stairwell--like an echo of an engine that used to thrum through the Missouri woods--and they know their father is truly home.